As a young man, Martin Luther King Jr. was struck by the absence of overt segregation in Connecticut. In summers of 1944 and 1947, as a high school and college student, King worked at a Simsbury tobacco farm.

In letters home to his mother and father, King wrote “Yesterday we didn’t work so we went to Hartford. We really had a nice time there. I never thought that a person of my race could eat anywhere, but we ate in one of the finest restaurants in Hartford.” Many years later, King discussed his experiences in Connecticut in his autobiography:

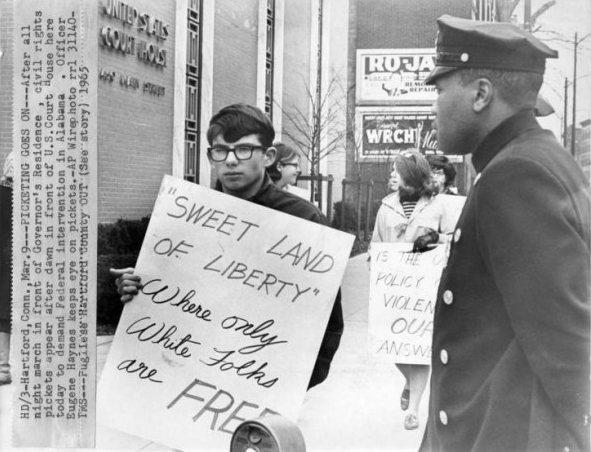

After that summer in Connecticut, it was a bitter feeling going back to segregation. It was hard to understand why I could ride wherever I pleased on the train from New York to Washington and then had to change to a Jim Crow car at the nation’s capital in order to continue the trip to Atlanta. The first time that I was seated behind a curtain in a dining car, I felt as if the curtain had been dropped on my selfhood. I could never adjust to the separate waiting rooms, separate eating places, separate rest rooms, partly because the separate was always unequal, and partly because the very idea of separation did something to my sense of dignity and self-respect.

Connecticut did and still does struggle with racial justice and equality, but two cases in particular — Gedney v. L’Amistad and Ross v. Schade are early examples of significant civil rights jurisprudence of which it can be proud.

Long before King and the civil rights movement and prior to the Civil War, a group of kidnapped African natives bound for the Cuban slave trade revolted aboard their ship, Amistad. While attempting to sail back to Africa, the men were captured off Long Island and taken to New Haven. What followed, beginning in Connecticut, was an extended, lengthy case in which the issues of human rights versus property rights were debated. Slavery was yet to be outlawed, and the bulk of modern civil rights laws would not be enacted for over one hundred years.

Long before King and the civil rights movement and prior to the Civil War, a group of kidnapped African natives bound for the Cuban slave trade revolted aboard their ship, Amistad. While attempting to sail back to Africa, the men were captured off Long Island and taken to New Haven. What followed, beginning in Connecticut, was an extended, lengthy case in which the issues of human rights versus property rights were debated. Slavery was yet to be outlawed, and the bulk of modern civil rights laws would not be enacted for over one hundred years.

Later on, a much lesser known rights case, Ross v. Schade, was decided in New Haven Superior Court in 1939. Connecticut law at the time allowed for a cause of action “in favor of persons deprived, on account of alienage, race or color, of the full and equal enjoyment of privileges of places of public accommodation, or discriminated against, on that account, in the price of the enjoyment of such privileges.” In Ross, the Plaintiff claimed he had been overcharged based on racial bias, and in violation of Connecticut statute. The Plaintiff, who must have pursued the matter out of principle rather than for the damages, prevailed and was awarded $.80.